Developed in correspondence with Victoria McKenzie

10 Limitations to Creating Our Freedoms – Freedoms that De- and Re-Structure those Limitations

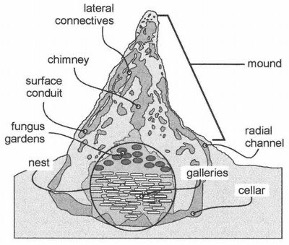

This collaboration began with a fascination with Termite architecture. Termites, utilising a specific fungus known as ’termitomryces’, create incredible mounds that proliferate in the desert landscape and redefine what it means to work with soil. Through a year-long correspondence, we unlearned, traced and re-experienced our relation to the soil and more-than-human communities—constructing and deconstructing with the material as well as with our memories, stories and experiences.

The collaboration of witnessing and working-with the garden led us into a practice of language and critical pedagogy of Earth, where we both engaged in “building” our notion of mound inspired by termite, and documented our observations and theoretical discourse that emerged through letter writing to each other. I was based in the Netherlands, and Victoria was in Canada at the time, so the act of working with our individual gardens and mounds at a distance became a ritual all the way through to our correspondence.

The work tapped into the critical act of ‘praxis’ which we believe is pivotal in the process of knowledge and learning and thus the process of architecture itself. We asked, what can it mean to ‘construct’, ‘deconstruct’ and learn-from the sensational pedagogies of Earth? What does it mean to listen and work-with more-than-human communities?

Back to Witnessing Garden 404

Performative reading and ceremony at the 'Learning from the Graden, Learning with the Land' public event organized by Piet Zwart Institute in the garden complex SNV

10 LIMITATIONS

1.

The project begins with an aspiration – an image – the termite mound. The termite mound is what we hold as a starting point within our differing localities, geographies, and “gardens.” The mound, created by the termite architects and a specific type of fungus known as termitomyces, is their home and is constructed entirely of soil which includes wood ligaments and cellulose. These architects redefine the methodologies of the soil, extending the notion of soil as more than “dirt” and instead a matter of co-living bodies. The first term and condition states that the materiality of the project is soil, and the image subject to construction-deconstruction is the termite’s mound.

2.

When we take soil (yet to be defined) from somewhere we choose and bring it to our mound, we carry it as treasure, as value; we carry it as a gift. We practice the relations of gift-making and gift-taking. A gift that stimulates a relation with the place we bring the gifts from. The gifts that are the foundation of learning processes and sharing or tending to thoughts, experiences, and places that are wrongly measured by an economic standard and are offered as emotional labour. These offerings are like resources for a construction: they leave a trace of the bodies and matters which fit life into other bodies and matters.

Extract from the correspondence

03 July 2022

Performative Reading selection

By the way, my mound is happening here, in front of the cottage entrance, on the land (three x two meters) occupied/covered by a shed. It’s the most typical allotment infrastructure in the Netherlands. These tiny houses, unequal in colour, size, and shape, point out an allotment complex. You can see sheds from the trains travelling between cities, these areas of specific intensity and lack of structure, stepping out from the regularity of clean fields of grass and glass. From the perspective within the allotment, sheds look just right. Even if the allotment is too small for a cottage, someone will find a place for a shed to store gardening equipment as well as toys, endlessly sophisticated barbecue tools, construction materials of any kind (or anything that can turn into construction material), and everything that might become meaningful in a household. As storage practice proves, not much is significant, and everything goes into decay. In our case, with the shed being at least fifteen years old, the whole construction slowly turned into ruins: the territory of fungi, bugs, slugs, spiders, and the household of rats of many types. Below one meter above ground, the wooden walls turned into a soft, constantly humid, dark matter. This chain of ruins and its appropriation by different garden inhabitants reminded me of something we discussed with you: all things and beings transform into soils; and, hopefully you understand my excitement of the parallels with our soil endeavour, it felt like the ideal location for the mound.

So the shed should come down.

Termite mound, research archive, Victoria McKenzie

Dear Victoria,

Here I am, aiming to share the observations of my mound creation with you. I feel the word witnessing speaks better about the process I am in: I am witnessing the observations, deciding which ones to take and how to capture them.

However, the first thing I wonder is how can you access the witnessing I’ve been doing without knowing me, the one who is witnessing? How, without introducing myself, can I be held accountable for the relationships I am about to share with you? It’s what Shawn Wilson says in Research is Ceremony (2008) about the cycle of relationality in the research process, in which the storyteller, or the researcher, is not a neutral examiner but a part of the relationships they encounter. The relationships between me and the garden’s living and dead condition my witnessing. Witnessing the examined relationships did not start at this moment of me sitting here, in this chair right next to the entrance door of my cottage, watching and listening, and documenting them for this correspondence with you. The witnessing started much earlier: with finding and setting a place for this mound; with inviting you into a dialogue about learning in the garden; with the moment when the project gained some tangibility in my head (and hands); with me starting to work in the garden regularly; with me getting this allotment plot number 404; with me moving to Rotterdam; and so on. There is no end to the beginning of this witnessing.

[

Dear Irina,

You are asking me the question of the witness. What it means to be the witness, a participant, an observer. Is it something passive or something active, or are these questions irrelevant as they collapse upon themselves? We’ve decided to encounter the process of creating the mound and within the mound is the material witness itself. You, I, the soil, the birds, the trees, the oxygen particle—the participants are endless but not invisible because, as you say, “witnessing the examined relationships has not started at this moment of me sitting here…”.

This morning I am thinking about time. The ways in which visibility and invisibility manifests in space yet “outside” of time—or perhaps, human time. The bird is a participant and will fly the skies dropping seeds on the mound; those seeds will sprout in the soils; and plants will emerge to attract more life—to create more oxygen. This entire process—both witness and non-temporal—exists along the trajectories of its own time or in the words of Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, a “multi-species time”. In initiating the mound, which I think is a better word than creating—are we also initiating time? Do we now participate in the initiation of various timelines in a way that allows for the extension of space? I think so. I like to think that as the mound rises, so too does a democratic space of multi-species action.

A space in which birds fly, insects speak, soil lives and humans move. A space of humility, of humus, where we encounter the things we never knew existed—the things that existed before us.

In the moments that you and I spoke, we said that the journey to the mound was as important as the mound itself. That the transformation of space, was also going to be a transformation of who we were in a way that ritualistic practice always transforms the user whether we consciously know it or not. This had me thinking on my walks towards the mound’s location—who am I? Where did I come from? How am I an accumulation of those who come before me? How do I reckon with my own history, good or bad? What are the small, perhaps unconscious, moments where I enter the personal-historical? The memories, the smells, the stories—the landscapes I love. These things fill my soul…

*******

a few years ago, my husband Vlad and I were debating whether we should build another shed instead of the old one. Right now, this idea sounds strange. However, it’s easier to be busy with an idea of constructing something than leaving the land empty. It’s a packed urban land we are talking about – the soil seen as a resource for construction rather than the living matter with which our, human, wellbeing is so entangled.

Every year I commit to allowing more uncovered areas in the garden. But apparently every tile comes as a devotion. It feels like each centimetre of uncovered land will require heavy labour. Will it? It will take some commitment, for sure. Despite the temptation to reduce the care burden in my life, every time I come to the garden, I am disturbed by too much concrete on the land even if so many tiles have been removed already. It’s a slow process of making time for tending to the ground. You cannot notice it all at once. What do I mean by the all exactly? I mean the relations between things and beings in the garden and how a new soil, even a tile size, will interfere in them. It’s an ongoing slow work of maintenance. [...]

Documentation of the Mound in Canada, Victoria McKenzie

Preparation of the space for the Mound, Rotterdam, Irina Shapiro

Documentation of the Mound in Rotterdam, Irina Shapiro