Developed in correspondence with Saša Spačal.

Editorial review by Cannach MacBride.

Narrated by Kari Robertson

Witnessing the Petri Dish: Speculative Knowing

Back to Witnessing Garden 404

A solution to stabilise the symbiosis between skin flora and environment in cases like Hagne's came from observations made by gardeners with CSD. These people developed the highly effective routine of a soily sensory diet, the only medically-proven treatment for this skin condition. It’s a tailored plan of physical accommodations based on skin contact with soil, developed to meet one's sensory needs. In people with CSD, the nerves near the skin's surface and in deeper tissues tend to react to epidermal bacterial symbiosis with particular sensations perceived by the human brain as skin discomfort. Rhizobia, the bacteria found in soil, is a key actor in treating such reactions: it activates metabolisms that support the best conditions for people like Hagne to experience their sensory sensitivity with less pain and discomfort. It's still hard to understand precisely how rhizobia's influence works in the soil sensory diet, if the bacteria fix the nitrogen and engage with the breathing mechanisms of skin cells, or if other actors of the soil community are involved. What is certain is that a lack of rhizobia causes negative and uncomfortable experiences in patients with CSD.

As soil farmers, Hagne and Cora came closer to their much-needed symbiont rhizobia: Cora needed to be in the earth for her night sleep, and Hagne needed a couple of hours a day in a soil bath to allow herself rest from the sensory discomfort that her skin’s contact with other materials and matters gave her. All of the farmers knew the ways of the soil most intimately, and through their senses they learned the soil’s qualities. They tested the dirt regularly, directly via their bodies.

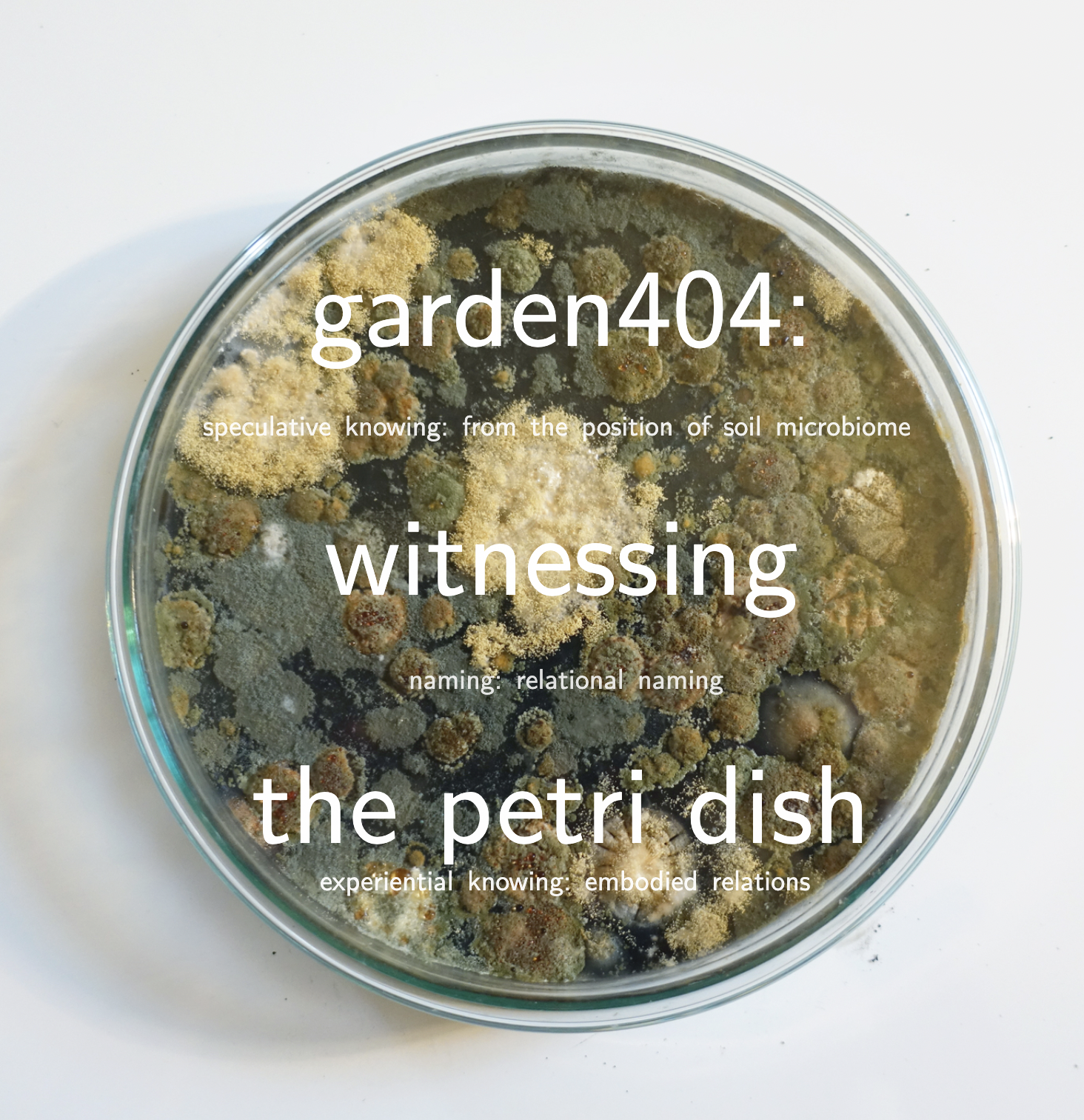

The farmers' testing methods were based on precise observations of petri dishes inhabited by soil microbial communities. Each day, as defined in The Land Steward Contract with the Department of Soil Regeneration and Human Health of the City of Rotterdam, Cora and Hagne would sprinkle some grains of earth onto growing medium in a petri dish and wait for microbial life to emerge onto the human scale of perception. After that they would linger for hours in front of minuscule landscapes, stare at fungal fluffiness, smell strange unsettling odours, and sometimes even touch the slimy biofilms. In order that their observations would not be contaminated by observations of the other, they wrote and scribbled. While collecting soil samples and writing notes they would also make images to share with each other and the wider Rhizobia Search Open Platform. Everything was prescribed in The Land Steward Contract, the protocols for collecting and sharing.

With time, Hagne and Cora became masters of sharing soil with each other and the wider community; looking for rhizobia in the petri dish, their perception shifted to the microbial perspective very quickly and almost effortlessly. Rhizobia was under red alert:: since the global change, due to monocultural and GMO production, variations of the bacteria were not able to form symbiotic partnerships anymore. Soil farmers were training to detect pre-global-change rhizobia which was still able to form symbiotic bonds and simultaneously enrich soil with nitrogen while supporting the edible corps.

Because of this, the endeavours of soil farmers were highly praised, but also tightly regulated since humanity's survival was likely dependent on their discoveries. But as Cora and Hagne became more and more attentive to the miniature landscapes, and slightly addicted to telling the stories the microbes whispered to them, they did not really feel the pressures of their everyday practices.

The Department of Soil Regeneration and Human Health of the City of Rotterdam developed a particular manner of observation that yielded the most rhizobia in the shortest time. Scientific equipment was scarce at the moment due to the breakdown of supply chains, so people with soil dependencies were employed since they were able through their symbiotic relationship to identify rhizobia from the pre-global-change times, which were non-modified and still able to form mutualistic bonds with plants and humans.

[

Traces of my actions enabling a small landscape to emerge. Pieces of soil I have left to grow, spread, and evolve into a community of fluffy, puffy networks, muddy piles of sludge and volcano-like microbial forms reeking nauseously. I wonder how the intra-action between the soil and nutrients contributed to the volatile molecules that are now entering my nose and triggering discomfort. I feel myself landscaping the discomfort. Travelling with my nose from one microbial attraction in the petri dish to the next, navigating the mouldiness. Slowly realising that my nose cannot discern the more stenchy organisms from less stenchy ones. It simply is not a good enough sensor for such a small surface, I am just too big and the world under my nose is too small. With my nose I cannot travel through this landscape, but my eyes see differences in shapes and colours and my mind knows that I am looking at traces of growth, traces of time materialised into beings – beings that are connecting and beings that are not. I do wonder if the empty space, the uninhabited agar-agar surface is really empty or just full of enzymes discharged as a warning sign to not come close. Maybe I should employ my hairy spikes to better examine the dish, but am I allowed? I need to consult The Land Steward Contract or maybe even write to The Department of Soil Regeneration and Human Health of the City of Rotterdam to make sure I do not break any protocols.

But I just cannot stop myself from translating between scales; to understand, I try to find equivalents of what I am observing in the human or planetary or some other scale that usually I don't even know how to name. In a lack of words I see black, brown, and white mountains and almost rivers in white bushes on the planet named the petri dish. I imagine travelling barefooted on the soft, sticky, suffocating ground of agar-agar, which visually resembles the Grand Canyon, but due to its softness is extremely difficult to walk. Imagination is feeling the unknowns, worlding a very personal petri dish, a very personal map. My vision has decided on an aerial view. Is it because the roundness of the petri dish reminds me of planets or because I do sense somehow the abundance of life and interactions in the same way as I used to when I was watching the land from an aeroplane.

The petri dish observations

According to The Land Steward Contract, §.II. Basic principles of petri dish observations, soil farmers Cora and Hagne of Garden 404 report the following weekly observations.

Date: 04/10/2121

Soil farmer: Cora of Garden 404

Title: Entering the Landscape, Finding a Map

[

Date: 04/10/2021

Soil farmer: Hagne of Garden 404

Title: Cloudy Landscape

What am I looking at?

It’s an emergence of visible and living material from a piece of dirt. Dirt that perhaps once was a plant, animal or human body, or part of another land and travelled to Rotterdam, and eventually became visible under the conditions in a petri dish. I started using the word dirt when I refer to the soil; it’s somehow as messy and unclear as my understanding of what soil is. Looking at the round shape of the petri dish, I am witnessing the transformation of this dirt into a new form; witnessing its beauty provoked by a changed state. I am witnessing a living matter meant to be hidden under the Earth’s surface. I can see the web formed by the thin white strands (or perfectly grey hairs) with black and transparent drops on the end of each stand. And I wonder where rhizobia can be hidden in this web?

I cannot judge if the thin lines set the destination from one piece of dirt to another; what I can see is that the whole space of the petri dish is packed with this cloudy soft substance. I might say that this landscape reminds me of a winter shrub, covered by a light layer of snow, and only a few berries stand out of this whiteness.

Is this surface as soft and fluffy as it appears?

Are those black drops liquid or crystals? Or some sort of berry-fruits, as my human associative imagination suggests? Although the smell that comes out of the petri dish disturbs this perfect winter view, it brings me instead to an abandoned basement, in which the mechanisms of decay turn everything slowly into the dirt.

Are the web-hairs with the drops-berries one sort of creature? Or am I introduced to a network of several organisms? And which creature that I am witnessing produces this intense smell of decay?

How long can the web grow? And if it grows longer, will the berries become bigger?

What will happen if I touch this cloudy softness? Is it going to collapse? Or will it restore itself after some days? Why am I afraid to feel it on the skin of my fingers? I wonder if touching breaks the witnessing and becomes a gesture of disturbance. It reminds me of little children’s instinctive behaviour when they care and are curious about someone or something; this tendency to touch, smash, and break whether it’s alive or dead, hopefully with the desire to understand and engage with. I also wonder why I am impatient to feel the soil on my skin to calm the burning sensation but afraid to touch the cloud that is just another existence of the same soil? However, even if I am trying to engage with the inhabitants of my petri dish, I cannot become part of them. One can wonder why I think of shrinking into the petri dish. I wonder if I can fully understand this environment if I cannot share it.

Sparks in the drops of morning dew blinded Cora as she opened her eyes in the meadow. Cora was an anaerobic breather, which meant she had a choice: while underground, immersed in soil, she could breathe nitrogen; while above ground oxygen was her preferred choice. Since she was of the soil, Cora’s body knew the rhizosphere and reacted to its moist lumps crawling with critters. When she inhaled the thick smell of petrichor, that wonderful smell of soil after rain, her hair extended into rigid spikes and, as her hair opened, it released at its tips smooth, slimy tentacles in search of rhizobia, precious nitrogen-fixing bacteria. The tentacles crawled through holes made by earthworms, pushed through humus, and wrapped themselves around the plant root nodules that were rhizobia’s homes. As they gently penetrated the nodules, Cora’s tentacles didn’t hurt the ongoing exchange between the rhizobia and the legume roots who were busily pushing molecules between them; nitrogen travelled into the plant and sugars towards the bacteria. The tips of her tentacles gently pressed into the spongy membrane of the nodules and joined the chemical correspondence, bringing a particular buzz of liveliness that sped up the flow between the symbionts. Because of this, her tentacles seemed to always be welcomed. It was there that she took her morning breath. Breathing in and out, Cora supported her need for connection with the underground critters as she was one of the people of the soil, one of the soil-dependent humans that could not survive above the ground. For her, this connection was as important as air.

While connected to numerous nodules with her hair tip tentacles, and breathing with the help of rhizobia and plants, Cora remembered the anniversary. A month had passed, a full glorious month since she had received notice that she was to become the land steward of Garden 404. Her soil dependency was a condition of her becoming a soil farmer, the condition that enabled her to leave the high-rises of the overcrowded cities and join the community of hybrids immersing daily in soil while caring and nurturing for earthy quality.

In the grounds of Garden 404 Cora met Hagne, a woman with a different type of soil dependency. Sensitive to touch, Hagne could feel every raindrop slide down her skin. As a little girl she could always be recognised on sunny days by the cloth wrapped around her body that prevented refreshing winds finding their way to her skin. While her friends ran barefoot on the grass, Hagne moved slowly with much care, discerning between different grass blades and leaves. Her body knew the grass as a crowd of plants, each with numerous textures waiting to provide her with different experiences. Hagne was born a haptic expert, and her experience of the environment was much more dense than that of an average human being. She had become an expert in what the world feels like.

Cora was mesmerised by the long and detailed descriptions Hagne gave of her deep and sensitive haptic scannings. Nobody could talk with such precision about things they touched; a leaf was half of a universe for Hagne. The reason for her acute expertise lay in how her skin's flora and fauna interacted with the surfaces around her; watery substances triggered particular flora to react, resulting in sensorial dissonance. Hagne had been diagnosed with the co-called Cutaneous Sensory Disorder (CSD), a name used to categorise people with supranormal skin sensations with no apparent diagnosable dermatologic or medical source. The price of Hagne’s sensorial superpowers was the intensity of what she registered – a feeling of burning, stinging, or pain.

[

I keep the petri dish open and exposed to light, so I can still see what is happening. I wonder if I observed everything I was supposed to, to contribute to the rhizobia’s discovery. Can I make sense of what I witness without shared experience or so-called expert knowledge? Feeling somewhat uncertain if my intuitive, romanticised exploration makes any sense, I keep staring at the opened petri dish, simultaneously dealing with the pressure of causing a change in the conditions of this environment. What information defines the significance of this landscape that I have been admiring for the last 30 minutes? Is it scientific information – the very source that I exclude from my observation? Or my visual (sensorial) experience of becoming aware of the beauty of the living dirt? What will happen if I know what I see on this so-called non-scientific level? What does it mean for learning?

Yes, it’s the learning desire as much as the survival need that brought me to this petri dish landscape. The composition, mediums, rituals, politics, and ethics of learning brought me to this witnessing. I am talking of the learning that becomes too abstract apparently for formal education and appears to be the core for the inter-relational bond between earthlings.

Failing to see myself part of the petri dish landscape, I try to connect to the soil of Garden 404 as part of the living network in which I am intertwined and with which I am dependent. Learning, in the way I understand it, becomes an everyday practice of interconnectedness of being that is mundane. Recognition of my dependency with this land lies in the recognition of the soil as a companion and co-maker of life as I experience it, or perhaps should say sense it. The recognition, attentiveness and (hopefully) care that build up my learning, are born in my embodied meetings with soil life; this learning seeks a knowing different from the scientific one.

However, the why and how of attentiveness and care and how they may arise still remain uncertain.

Do I learn because I care? Do I relate because I care? Do I care because I am dependent on what I care about?

Learning is a both-sided ritual: it changes the one who learns and the one who is learned, as the latter receives a new representation from the learner. Simultaneously, the learner’s reality is re-shaped by the researched reality. The reality I am learning about – the land of my healing garden – unpacks and complicates simultaneously with the act of preparing the petri dish, even before the observations have been started.

There is the first principle of the ritual of learning – making time for attentiveness to the dirt.

The second principle is to find myself in-between myself before the learning and the dirt’s networks of balance between life and decay, which emerge in the petri dish. This position is the place from which I witness what I can witness; I experience what I am able to, and I care about what I commit to.

Commitment would be the third principle of the learning ritual. My commitment to my dirt is perhaps my best chance to access the researched landscape of the petri dish and meet rhizobia. The commitment allows me to think of the care networks built inside and outside the soil – human communities of practice around the soil, which I am apparently part of through my dialogue with Cora.

The fourth principle of the learning ritual is to be simultaneously an individual and collective meaning-making journey.

Learning is also a both-sided process because it’s embodied and intellectual simultaneously. The dirt I know, relate, and am committed to differently cannot be the same neglected dirt under the city's concrete surface anymore.

[

Date: 11/10/2021

Soil farmer: Cora of Garden 404

Title: Traversing Timespaces: Sometimes Somewhere

It seems I am observing a world. The world of micro communities with different morphologies, but from afar, almost unthinkably far. Maybe in a human time scale, I would be looking on to Earth from another galaxy. The time-space of these tiny dwellers is very different from my human perception. As I write these two words “tiny dwellers” my emotional connection to the petri dish gets filled with care. A connection to my first years on this planet emerged. As a child I used to collect films and TV series that featured tiny human-like figures. With the words “tiny dwellers,” the inhabitants of the petri dishes connected to my emotional memory and elevated my feelings to nurture and protect. I am becoming a petri dish carer. I know I can barely see the dwellers but I do relate, after all they help me breathe each day.

Watching from my timescale, the inhabitants of the petri dish have hardly changed or evolved in a week, but then a thought: Who am I to comment really? I am extremely far and do not even perceive clearly in the time-spaces of the tiny dwellers. Their communication and any kind of meaning-making tools are certainly not visual and audible but uttered through chemical reactions in the form of enzymes and metabolites. However, maybe I do smell some of them?! I do, but unfortunately there is no transformation in time perceivable to my nose. Tiny communities of the petri dish seem to emit the same odour as last week. Still I am very far away and to be honest my nose doesn’t really remember well in time. Since a week has passed, I can only really guess if they do smell the same. The fleeting nature of smell takes my ability of distinguishing away since I can only define a smell by comparison and difference in one particular time-space. It’s a pity I have never before smelled pre-global-change rhizobia, now I need to learn the long way by trying and comparing.

Even if the tiny dwellers have changed, I can’t perceive their change. However, due to my observations of the growth and evolution patterns of various petri dishes in previous experiments, I do believe they have gone through transformations and are performing their life-maintaining processes, just not in my time-space, but sometimes somewhere in their own time-space. How will I ever find rhizobia sometimes somewhere?

[

Date: 11/10/2021

Soil farmer: Hagne of Garden 404

Title: A Landscape of Remembering

A box of soil with whom Cora moved into the garden stayed here for a month. I watched it absorbing rain and, I believe, slowly dissolving with the native soil of Garden 404. When the time came for the petri dish observations, I took five tiny pieces of this mixed substance to grow in one petri dish. I mixed another part of Cora’s soil with the water from the garden’s pond and left these samples in the second petri dish.

While the emerging landscapes from these different samples looked similar last week, the mix between water and soil turned out to look so different today! The images and smell of the landscape I am witnessing bring me back to this site with the river, surrounded by swamps, fields, and hills, Moscow’s suburbs, where my childhood summers were.

Back then, I would have only one or maybe two toys – I knew them by name, of course – but endless scenarios for play, in which food, plants, soil, rocks, broken construction materials, and housewares, could be transformed into unexpected but fundamental valuables. The precariousness of the family of doctors and scientists that I am from, living in the ruins of academia and the health care system after the global change, was not an obstacle for us kids in our ways of relating and, hopefully, learning. In the late afternoon, negotiating between coming home for dinner and continuing playing, some plants from our game elements slowly transformed into food. In the event of an accident, some of these plants appeared to be cures that could stop bleeding. For us, nature was full of openings: the trees, plants, animals, all we encountered was one fluid world built on observations, practical needs and simultaneously speculative stories.

I recently tried to recall these childhood memories during a visit to a medical herbs garden in Rotterdam. What were these creatures we ate when hunger hit us as kids on the road, or applied when my sister would climb this hill and, of course, badly scratch her leg on the unexpected wooden branch? Back then, we were of the land, which somehow emerged in the petri dish’s landscape of the soil mixed with the pond’s waters. Each of these yellowish and reddish hills would have a name and a role in our games. Each rock was a companion, a teacher, or a destination we desired to reach. Each grass could be a bed, a doll, or healing matter caring for us in our failed endeavours.

They were living participators in our lives, and our lives depended on them and our shared land. Every new horizon was desirable, inviting, and scary at the same time. We knew the taste of many plants, berries, waters, and rocks: when you are on an expedition, you try to think of companions who allow you to hide the longest, reach the most challenging point in the swamp, and find the rarest flower in the area. We cared for these friends, as much as kids can care: we protested against any tree cut, fires in the forest, and we buried our animal or bird companions, even if they were meant to be on the dinner table of our neighbours. I am sure my friends and I, as we were back then, would find the best way to discover and partner up with rhizobia!

But I wonder why this combination of belonging, learning, and care was experienced in play? Play that was led by curiosity and not spoiled by fears of looking stupid, immature and unstructured, too fragmented, or not methodologically cohesive. Can I continue the observations with play in mind? Can these observations lead to a playground that would allow me to become part of the Garden 404? Can I bring this play as an inquiry to my learning practice?

>> The soundtrack can be accessed here

[

Date: 18/10/2021

Soil farmer: Cora of Garden 404

Title: Dark Chocolate Biofilms

The soil particles have morphed into brown and black slimy moulds, the biofilms on their surfaces have become thicker. The bacteria is proliferating moderately and the smell has become even heavier and incredibly thicker. Is this it?! Is this rhizobia? It’s reminding me of old, wrinkled, earthy smelling cheeses I encountered at French markets some years ago.

While observing the petri dish, I realised that trying to observe without scientific knowledge of bacterial and fungal morphology is a bit difficult and also sometimes doesn't make sense to me. Just simply knowing what bacterial colonies and fungal networks look like seems useful in some moments, but I wonder how much gets lost or left out when applying only concepts and cartographies of classic scientific inquiry.

I would dare to say that if I were to imagine myself as of the petri dish, I would still know these facts, I would know the flora, fauna, fungi, and bacteria that surround me. I would most probably give them different names according to their smell, look, or particular usefulness, maybe even designate them with a status of sacredness or entangle them in my rituals and everyday practices.

The difference would be that I would form a relation to these beings somehow, with naming, use, or ritual practice. I would be with the inhabitants and landscapes of the petri dish. But that wouldn't stop my curiosity and passion for interpretation and understanding my cohabitants. I would observe as much as scientists do, I would just be more in the world, in the entanglement and direct contact. A bit more vulnerable, but a lot more grounded.

I wonder why the bacterial biofilms with its shiny surface of goo reminds me so much of melted dark chocolate. Oh, if only it would smell like that …

Date: 18/10/2021

Soil farmer: Hagne of Garden 404

Title: The Invisible Mesh

It's getting cold in the garden, inside the cottage as well. For the last month, this cottage has been a studio of mine – not only as a soil farmer, but as a teacher. I am supposed to work here, meaning to learn, teach, and reflect. Since I came to this definition of work, the work has shifted; now, the teaching and learning include gardening and soil making, searching for names of plants in catalogues, composting and taking care of the worms, fermenting, witnessing, and hoping for rhizobia with the fellow Land Stewards.

The cottage is the place where the petri dishes are. This time observing the petri dishes, I take them from the dark shelf where they live; I am bringing them to the light, I open them. It’s the time of the year when the sun does not rise too high and shine into the window, so to see through the petri dish if I need to direct it against the sunlight. I like the graphics of what I see; it's not a landscape any longer, I guess, it's a map – the map of a mesh. Bringing the petri dishes into the sunlight, I see the connections and relations that are unseen if I look otherwise. They are hidden by a layer of a substance; either the petri dish culture or something that has grown since last week. I should not be surprised: in learning (or teaching), there are always connections you cannot see at the first glance; it is always a perspective that needs to change in order to see something new. This is what I hope for the rhizobia observations: various eyes, perspectives, and interpretations will eventually witness what we, people of soil dependency, are seeking to witness.

The softness of the cloud I celebrated during the first observation is gone. Now I see several layers of nets and dust rooted in one substance of the petri dish. I wonder what I am looking at? Is the soil decaying after a flourishing moment and transforming into a new type of soil?

There is something simplified and simultaneously more intense in the dish as time passes. Is it decay or maturity? Does the landscape I look at represent several generations of creatures that change and enrich this petri dish universe? Or maybe it’s the traces of the newcomers that grew on the dead?

Or is it a memory that keeps overwriting itself and creating this dusty effect? It looks like a window in an old house that lived through the dust and rains of several falls on its surface. Spring’s snow and rains tried to wash away the traces of fall, leaving organisms that attempted to inhabit the glass. Is it their memory that we see? Their decay? Their soils?

[